New Burlington, Ohio: When A Town Dies - The Craftsmen

The Craftsmen: the old ways.

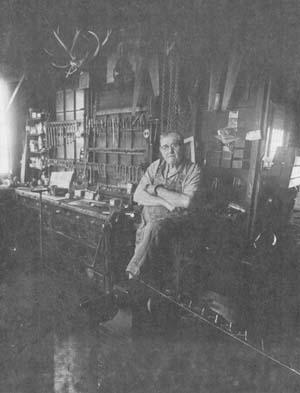

The blacksmith shop is in the farmland north of the village. It was not the oldest blacksmith shop in the New Burlington farming community, but it survived to become the oldest. Hugh Lickliter built it behind his house in the first year of the great depression. One eye consulted the failure in the nation, the other regarded the rich New Burlington fields. If the shop faltered, he would make it into a double corncrib: nations rose and fell, and the fortunes of men, but the fields went on forever. In the spring, the plowshares piled halfway to the roof. Howard Pickering, fifth generation blacksmith, came to work and stayed forever.

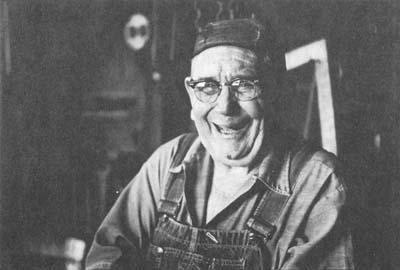

Hugh Lickliter is not a big man, but his crafty leanness implies the blacksmith’s strength that Howard Pickering states. Both give generous testimony to the mythologies of hard and frequent work, although younger men who worked as hard lie in the cemetery to the south.

A month before Howard Pickering’s sixth birthday, he jumped from a haymow, and landed on an upright pitchfork. He remembers that he died. “I pulled the pitchfork out and I can hear today the sound the tines made coming out of my stiff overalls. I died while the doctor was coming. He swung me by the feet and the blood went to my head and I began again. They put me on the kitchen table and took out my intestines and washed them. Four men held me. D.M. St. John, an old farmer, came to the house the next morning at four a.m. and told my mother to make a batter like bread dough and she did and he told her to put the pitchfork in it and bake it several hours and she did. I was never bothered no way from that day. I don’t know if there’s anything to it. But it happened that way….”

Afterwards, he found he was independent, and very nearly fearless. Because Hugh Lickliter, who has an Irishman’s fabled disposition but German blood, is largely the same way, they worked together for 35 years. The nature of the work changed slowly, and the beguiling slack of time became anesthesia to the change itself. Now in their middle seventies, with the forge heated only on the sporadic days when some odd work piles itself on the fire-darkened floor, both feel the change, but view it mostly as spectators. Old age is an arena, and softens the king’s judgments.

Howard Pickering perhaps feels it more because he is a fifth generation blacksmith, a man of rare continuity in any age. His grandfather, a blacksmith and wheelwright, came from Missouri in a wagon he had made. “None of my sons became a blacksmith,” says Howard Pickering in a tone that combines both relief and loss. “It is a fatal work, blacksmithing. It has run out. I feel that….”

“How are you, Mr. Pickering?

“Well, I ain’t hit my fist….”

His grandfather recalls a neighboring wheelwright who filled an ill-matched groove with putty, which was noticed by the old wagon owner. The wheelwright explained that upon hardening, the putty would be as strong as wood.

“Then why,” demanded the old wagon owner, “didn’t you make the whole damned wagon out of putty?”

Howard Pickering likes the story because it is at once humor and fable. Neither he nor his grandfather would have considered putty, not because the substance was incorrect but rather the idea was.

He rolls the sleeves of his work shirt to reveal terrible scars up the inside of his arms. They look like the fury of unskillful suicide attempts.

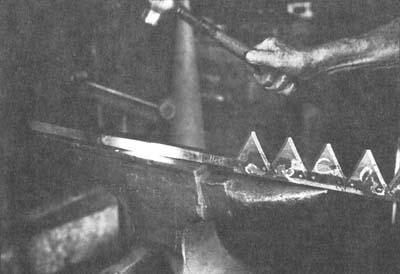

“See these?” he asks. “It is from making wagon wheels. God, I liked it! It was hot and furious work, beside the flame and in the smoke, but what a fine and particular piece of work!”

Hugh Lickliter also has scars. His are on his stomach, from working the forge without an apron, and the hot metal flake bouncing off his skin. The residue of Hugh’s independence is a quick temper moved by a quick tongue. Because the price is high, only an independent man can entertain such character. Behind it, however, is also a quick mind. “Two can live as cheaply as one,” he says, ”but one of them must quit eating….” He chews Workman’s Choice tobacco and spits upon the coal pile. Although he has lived into a modern time and made adjustments to it, he is not a modern man. Both his style and substance come from the injection of an old and Calvinistic medicine: much work, no waste. Hugh drove his Chrysler 23 years, then retired it to the barnyard like a faithful animal. Its great antiquated grill still gleams through the barnyard weeds like the waiting mouth of some steely predator. He thinks that playing the anvil with his hammer makes a nice display but that it seems mostly a waste of energy. “It sounded pretty, though,” he says. It is a minor concession. Hugh will never play a tune upon his anvil. His motto is: “you do not appreciate a chain saw until you have used an ax.”

“I do not know if a man inherits hands,” he muses. “A man is perhaps born only with a desire. My uncles couldn’t thread a needle. No one in the family was a blacksmith. There are perhaps two inclinations. If your father was good, you may be inclined to be as good as he was -- or so disgusted you don’t want to hear about it….”

If the work stands as expression, there is no need for talk of philosophy. Everything is contained in the work. Hugh Lickliter, then, handles the obvious with a refined country humor: “The art of my work teaches me how to do something well with less work. The first thing is, you don’t want to pick up hot iron….” When Bob Collett asked him why he was late for church, he replied, “Well, I expect it was because I didn’t begin on time.”

Over the years, a subtle ritual established itself between the community and the blacksmith shop, although none would likely recognize it as such. When the boy children reached the edge of manhood, a time intuitively sensed by their fathers, they were allowed to come to the blacksmith shop with their fathers and listen to Hugh Lickliter and Howard Pickering fill the air with their eloquent profanity which in its quaint, old-fashioned turn, became not profanity finally, but another language, addressed to the work itself, the two smiths keeping company with each other, and the faith of their work. The fathers, with their unspoken compliance, told the children: you are of age. The salt in the old blacksmiths’ English preserved both the work and a continuity in the neighborhood.

The shop is closed most of the time now, however, and only the older men know the two blacksmiths.

I’ve worked at blacksmithing since I was a kid. I never took an apprenticeship but I talked to a lot of the older ones. They were all my friends because I was never ashamed to admit that I didn’t know everything. They took a real pride then in their work although now it seems that the sloppier a damn fool can be the more he’s respected. We now put out work anyway to get it done. We are sloppy, and automatic and we end by scrapping half of it. We don’t get anything right down to the scratch, and we don’t have real mechanics anymore. We have parts men. They take off one part and put another part on. Now there are machines that determine what is the matter with other machines and I just don’t know about it. There used to be a type of work that a man took pride in his ability to see it through but now one man does this, another man that, and when it’s finished, no one knows what he’s done nor has any authority about it. A man has no interest but in pay day and quitting time.

My father came here from Virginia, and we’ve always lived within 20 miles of here. ‘Lickliter’ is German, but it has no special significance that I know of. It was once spelled ‘Leichliter’ but then it was changed. My grandfather was a cabinet maker and undertaker. When someone died, he would measure the old fellow up and make a casket that very night. It sounds farfetched but it’s true. And he worked with walnut which would be worth a fortune today. He had the lumber planed and ready and I remember once that someone asked him for a casket made of cheap lumber and he refused the work, although I don’t know the details of it.

My dad was a good man but he didn’t stay put too long. When he was broke he came right back, but when he got on top he couldn’t stay there. I think he wasn’t a good businessman and made mistakes but who among us haven’t? He liked race horses and that was no poor man’s hobby unless he had money set aside. When I was 11, he harnessed a team for me and I ploughed in the fields, out there on the hillsides. I had to do it and so I took it for granted although I was young to be handling a team. Some say it is a lie but I know because I was there. It was a gentle team and they did what I wanted done. Of course, when I got to the end of the row I couldn’t lift the plow out to swing it around. I had some of the awfulest looking ends. Once I ploughed in under a root and I was so small I couldn’t do anything but unhitch the team. When I was 13, we had a little blacksmith shop on the place that wasn’t used a great deal and I made some shoes one day and shod the pony. When dad got home, Mom said, ‘Hugh has shod old Joe,’ and dad jumped right up. He thought surely I had driven the

nails too high. I didn’t drive them very good, I admit, but they were still on the next day. I liked that, and I’ve worked at it all my life.

I worked on A.E. Beam’s farm from 1921 until 1929, then I bought this little place and set my shop back here where I could throw it into a double corncrib if I didn’t make it. When the depression happened, I was like all the rest: I had no money in it, and the stocks went first and men killed themselves I heard but what were stocks to me? It was later, in 1930 and 1931 and 1932, when men were unemployed but this kind of business thrives in bad times because no one has money for new things and so they repair the old. We got enough in to keep going and we put the rest on the books and when they got it, they paid me, with the exception of two that I remember. I had always wanted a little shop and now I had it and 11 acres, and we survived the depression although we had very little money, but we lived, and as time went on, things got better.

One spring, I don’t remember which, the ground turned dry and we had 283 plowshares on the floor at one time to be sharpened. There is nothing like a hard ground to wear them down. We usually did 15 or 20 a day and we shod a lot of horses and did a lot of wagon work. If a man is lucky, he can sharpen a plowshare in three heats. It was an awful job to hammer a plowshare out by hand, but I’ve done it, although soon I paid $325 and got a jig hammer. Now it would cost $2400, and there’s an art to it either way. The walking plow shares had to be just right or they wouldn’t run. If they were not right, they’d kill a man. It would pull, go too deep, Lordamighty. A tractor, now, it just rams a share in the ground and no one knows right or wrong, but the man after a walking plow knows. All walking plows were left-handed, and when the tractor came, they turned to right-handed, and did the blacksmiths cuss at that. A left-handed share, you see, threw the ground left so your lead horse was in the clean furrow and the others on the unturned ground. It put your team on the land. I’ll be damned if I know why they changed as they did. When the blacksmiths sharpened the left-handed ones, they could lay it up and hammer it from underneath with no trouble. But when it changed over, it was the other way around and awkward. It was the change of it. It was hard to work with smoothly because it was all backward, and the older ones took a pride that no hammer marks showed on a share and now it was damned near impossible! With the machine, it made no difference, but by hand it made a big difference. Now it makes none at all because they’ve done away with the sharpening. We do a few but most buy shares which last five times as long and they’re cheaper. The old ones cost $6, the new ones $2.85, and I don’t miss it.

I’d rather shoe a horse, though, than anything. To do what another man can’t is my consolation and can’t everybody shoe a horse, not by a long shot. If you don’t believe it, you should see some of them trying it. Some horses will bear down pretty well on you, great Godamighty. Once I got the hell kicked out of me. I went down to pick him up and he found me off balance and they say he whirled me three times. It stove me up a bit but I was younger then so I beat the hell out of him and shod him right away. What you have to do is let him know you are there, go down his side to his leg, pick it up and get your leg under his so he can’t kick. That doesn’t mean he can’t jerk, don’t think it doesn’t. Sometimes we’ve shod two feet at a time, one at the back and one at the front on the other side. The horse has to be decent, of course, so it’s not often practical, but we’ve done it. Many a day, we’ve shod two teams in the morning and three more in the afternoon. Sometimes we quit at three and sometimes it was after five. It all depended upon how the damned old horses stood. They would kick and some would jerk and others would lay down on you. I have been around horses a long time but I’ve never seen anything to admire about them. I don’t like them, although I liked the shoeing. A lot of men make a great to-do about the affection of a horse, but I found it like an old man once said: all whiskey’s good but some is better than others. I never myself saw the difference.

We used to shoe a number five for $3.25 and a number six for four dollars and now it is ten or 12 dollars for a number six and maybe $14 some place. Number six is a great big shoe and number four is lighter and double-ought is for a shetland pony, which is the meanest thing in the world to shoe. You can’t hold their legs up because they’re so short and most all are bad-tempered. They’re for kids and they do as they damn well please. I never did any fancy shoeing because all our trade was work horses and that never took great brains. There’s more of an art to shoeing a race horse, and as much difference as night and day. You have to balance his feet and trim his hooves just so or he’ll hit his knees or his back feet will overreach and hit his hocks. It’s quite a job to know that and we never went into it around here. Most horses, however, I can most often look at the foot on the ground and work it right out on the forge. Oh, maybe I have to hit it a crack, then she’s right in there. of course, I haven’t done it now in some time because the best part of me is over the fence, and today I might have to stick their feet in a bowl of plaster to fit them.

No one makes big money here. It would be hard to average $4 an hour, and in a factory you’re getting paid whether you’re working or not. I’ve just been content with a living, because what is a million dollars laid up in the bank? A lot of people have missed their calling, working every day and hogging up every dollar, but our standard of living calls for it, I suppose. I have serious thoughts of our country and I have my opinions of it although I may be 100 percent wrong. I think a lot of people work that are not adapted to it. They do it and they don’t like it. You have to like it. I’ve never taken a job I didn’t like, and I’m no different from any other man. It’s the fact that I liked my work and maybe that’s a stupid streak, but that’s what it depended upon. If I didn’t care for it, why, I’d be mad when anybody came to me.

You have to start back to know why. People began saying, ‘I don’t want my boy to be like me. I want him to have a good job and not have to work like me.’ There was no encouragement for him to be his own man. Then he’s married and has to have a new home and an auto, and he goes to the bank and it’s all done and there isn’t a great deal of satisfaction in it somehow. There are no sacrifices except the bank has you tightened up, and to my way of thinking, there are no values in it. We start at the top rather than at the bottom, and the attitudes are all different. I started pretty moderate when I was married and what we got, we sacrificed for it and we knew what it was.

We began with $11 and a table, and it never bothered me what my neighbor had. I’ve been satisfied with my lot. If my neighbor has something better, why, then, I’m glad he’s my friend, and I can go look at it. I never envied no man or wished I could do what he did because I did what I wanted. I have admired those that accomplish more than I. At one time around here it seemed that nearly everybody bought a new automobile. I admired them, but mine got me where I wanted to go. Autos are all made to run and transportation’s all you get from any of them. I never fell in love with any material thing too much because anything you can replace don’t have such a value to me. I think there is a certain degree of envy among people and always has been. If one man gets, the other wants. That is the attitude. He doesn’t think of what it will do. It’s just his neighbor and it continues until this day and it is a pisspoor way of doing things but it seems a general attitude or something close to it.

I had a Desoto I bought in 1948 and I drove it for 23 years. I ground the valves on the little fellow, at 100,000 miles I over-hauled the engine and bored it out and drove it another 60,000, then I retired it to the barnyard. I have neighbors that trade cars every two years and it costs them about $1800. I go just as far as they, and it doesn’t bother me. I spend money because that’s all it’s fit for, that’s my attitude, but I won’t spend it so that charity will have to bury me.

I was 75 this past October and I’ve been very well satisfied. I’ve had aches and pain but I’m not broken down, and the work has helped. I’ve never worried about anything. When I close the shop door whatever is there remains behind until the morning. I don’t think about it and that’s the truth. My wife, she worries, but I’ve never seen it do her any good. It makes her cross sometimes. If I’m responsible for error, that bothers me. But nothing else. Why, I’ve a neighbor that worries about the weather! He frets and stews and fumes, jiminy good God!

I haven’t been the easiest fellow to get along with. I’ve said things I’ve regretted. I’ve been critical of work that goes out and I’ve criticized too severely. But that is the way I am. I’ll raise hell but I’m no man to hold a grudge. Twenty minutes later I’ll drink beer with you if you want to drink.

When I was young, I learned to enjoy what we had right around us. I was brought up that way. What toys we had we made ourselves and we appreciated it more than buying them with no effort. Kids today don’t appreciate a cussed thing. They take it for a matter of fact that they have things. Happiness is being content with your surroundings and entertaining yourself. It seems to me that there is where many fall down today. My ancestors earned their keep as they went along and most lived and provided. It took hard work and what is the matter with that today? But today it is ‘Dad, I want $25 because I’m going on the town.’

My work is a small service in this world, to my neighbors and friends, and they’re glad I’m here when they break down. I’ve made a living from it and I’ve liked the work. I’ve tried to be reasonable in my prices and I’ve caught hell from my competition but I’ve always charged what I think it’s worth and what I would pay for the same job myself. I’ve not accumulated anything but I’ve lived and enjoyed it. All that counts in this life is to be satisfied in work.

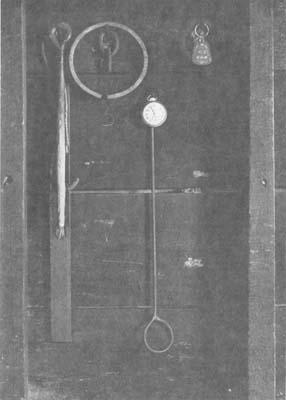

I am the fifth generation of Pickering blacksmiths but it is an antique trade now. The wheels and wagons and horses are gone now, and so is the work. We do a few plowshares still but that is all. Today, most plowshares are throw-aways although there are those who bring us a few of them to sharpen, and occasionally we get some of the old ones. They are from old two and three bottom plows for those that don’t farm real heavy. The shares just get so dull it takes gasoline as much again to pull them in the ground. They’re hard to sharpen also. Too much heat and they warp and you begin again, but like everything else, there’s a knack to it. I give them all a little suck to make them run right. Right on the point, just make it bend down a little for a little clearance under the landside holds the plow in the ground.

I’d rather shoe horses than anything I’ve done because it fascinates me. I like to smell the hoof burn against the hot iron although most hold their noses and run from the shop, and I love the sound of an anvil. My dad could drink more water than any man I’ve ever seen and when he wanted a drink he would hammer on the heel of his anvil and you could hear it a mile. He wanted a drink and we knew we had better be there, for people made their children mind in those days, and so I grew up to the sound of the anvil. When I was eight or nine I stood on a box and pumped the bellows for my dad, using a buggy shaft for a handle. I was always about the shop. I was clinching when I was 12. It is done with a clinch-cutter which cuts the horseshoe nail off square, then it is rasped smooth. A lot of horses have a spur on the inside of the hoof and that, too, has to be rasped down. Dad would drive the nail in and leave the clinching to me. At 15, 1 could do it all. It came a fierce sleet around Christmas the year I was 18 and I shod over a hundred horses during January. What work that was! Listen, they never invented anything to make it easier although some of it is gifted to a man. A good blacksmith can watch a horse travel then shoe him right. I’ve seen two do that. Stanley Dancer the race horse man had a German fellow, paid him $30,000 a year and called it cheap at that.

My grandfather made wagons in Missouri, then he came to New Burlington. If a thing was to break, a blacksmith shop was where it came because you just didn’t go out and buy things new every day. Hooks, singletrees, tongues, open rings, chain, all these things were made by a blacksmith, not bought off a shelf. Grandfather Joseph could make anything. I have hammers and tongs now made by his hand. He sharpened plow shares for fifteen cents and shod a horse for thirty cents a shoe and I have his ledger to prove it so. I began working regular with him and my father in 1910, when I was 12 and our work was mostly wheels and horseshoes. Who could make the spokes in a wagon wheel today? We made everything but the hub. Grandfather made the spokes of hickory with a draw knife and a wood rasp, with a tenant-cutter for the ends. It was a very particular job. That was my grandfather’s work and he died in 1913 and I do not believe he ever saw an automobile.

My father was a very particular man and I was glad of it because he taught me that anything worth doing is worth doing right. He would sharpen a plow and it would run clean across a field and no one had to hold the handle. When I was six he made me a sled out of a pair of buggy shafts and it was never beat down a hill. When he bought buggy shafts, he always bought three. When you put one in, you’d do three. No one knows why but that seemed to be the case. He never worked on an automobile. He was the afraidest man of gasoline. When he rode with me he rode with his door open, ready to leap if things went wrong. Well, all of the younger ones wanted an automobile. It was something to get hold of. We were like children after a toy. I drove a huckster wagon when I was 16. 1 got in there and just gripped the wheel as hard as I could. I ran it a mile and it got away from me and into a ditch and back the other way, by golly! My father finally bought one, but he was very afraid of it. He had some age on him then and when you have that, there is such a difference in the speed of things.

When we were young, why, none of us ever thought of what the automobile would do. Today, having the choice, I’d do away with it. The horse and buggy days were the best of my life.

In my day everybody had a driving horse. Dad had a grey mare never beat on the road. It was 10 miles to Xenia and Dad could drive there in an hour and it took a good horse to do it. In those days, you meet anybody on the road and him with any speed at all, why, a race was on. Then I had the smartest horse I ever drove. I’d be asleep and she would ride into the yard, go to the trough for a drink, then back up and turn left so she wouldn’t catch the buggy wheel on the trough and go to the barn. Dad raced her one night and she struck her knee and the next morning when mother went out, she stuck her leg straight out the door to show mother where it hurt. I always liked horses because I was raised with them. I did all my running around with a high-life horse and a good buggy and they were pleasant times because everybody knew everybody else and you left your doors open and people didn’t steal everything you had.

We never turned away any horses to shoe and that was saying a lot for those days, but my dad died at 57 because he had shod too many mean horses. They claimed that everytime a horse jerked you it enlarged your heart. I missed part of my first year in high school when a mule kicked my father and broke his leg and I went into the shop. I was kicked some, and I’ve caught a few nails, but when they kicked I always went into the horse and not backward and I wore a thick leather apron which cracked like a board when I was kicked. Once a big horse caught a nail under my ring and fairly led me around on my knees. I never wore one again, I’ll tell you. I remember my dad resetting a mule’s front shoe and getting his cap kicked off with the back one. He just threw the mule down in the lot and someone sat on the mule’s head while dad finished with the work. He charged fifty cents to reset two shoes instead of the usual thirty-five and the fellow really hollered about it -- but he wasn’t there when the work was being done. Old Amos Faulkner had a team and like most teams there was a good horse and a bad one. The bad one, I could have killed her twelve times and so could have my dad because she would just piss all over you. To keep her still we would roll both her ears with a rasp and put a twitch on her nose but the piss was something else, yellow like an egg and gallons of it. Well, you have experiences with anything you do in life and that was one of them.

I had six brothers and a sister and seven of my own children but no one learned smithing but me. It was getting away when I was small and I would have been better off doing another job. I worked for Hugh Lickliter for 35 years just for a living and I made Hugh his money and although he didn’t raise his prices nor my wages he was the best man I ever worked for. I was offered a job welding in Dayton once but my family didn’t want to move and I didn’t want to change and with that against a man, he can’t do much. I worked in the factory at Frigidaire only briefly but I am hell on those kind of people. I cannot get along with them. After ten months I was laid off and although I could have gone back later I never did. The foreman didn’t like me from the first. He would say, ‘Come on, blacksmith, get the lead out of your ass.’ And when I left I said to him, ‘If ever I meet you someplace out you’ll have to be a better man than I….’ Oh, there are a lot of bad jobs in the world. Once I was offered a job with the state and the man said, ‘You’ll have to divvy up at election time,’ and I looked at him and told him where he could lay his job. I guess I just headed that way when I was young. There was always too much temper about me. But I liked the blacksmith shop although with seven children I never had the money to own my own shop. We got by and part of it was hard getting by and I don’t know how we did it. I worked thirty years and not two weeks’ vacation. I just took the money instead. That was how hard up I was. To work for myself, now, that means keeping book and with Gilligan wanting three cents of every dollar I just think better of it. Blacksmithing has run out. I feel it. It’s quit off and I am 73 years old and when you get old you hate to begin anything new. But my grandfather used to say this: only two blacksmiths ever went to hell. One didn’t charge enough and the other hammered cold iron.