The Imports

There was a time when America's game was played by only three kinds of people: White Americans, black Americans and Latins.

It goes without saying that the experience of white Americans in major league baseball is well-known. And, while early black players were grossly underpaid and exploited, their integration became a noble act that benefited the nation as a whole.

But from the very beginning, Latins have been bystanders - present but in the background, one step from greatness, a translator away from notoriety, a heartbeat from poverty, and a world away from home.

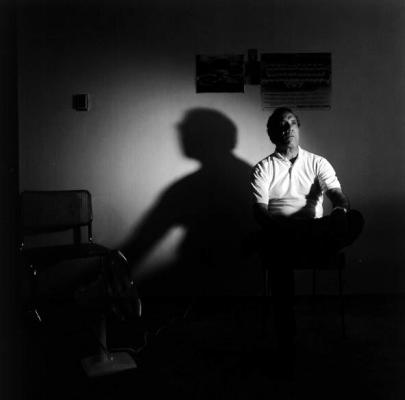

"We are like some stray dog, like some rudderless ship at sea," says Tony Oliva, a Cuban who won three American League batting championships with the Minnesota Twins between 1964 and 1976. "This is what Latins need to learn early to be able to live and survive in this business and in this country."

It has always been this way. A case in point: In 1945, when the Brooklyn Dodgers were looking for a black player to break baseball's color barrier, they considered an amazing Cuban shortstop named Silvio Garcia.

Imagine the history. The first black player in the major leagues - a fiery, colorful star from the streets of Havana.

But Garcia was dropped from the running, primarily because he couldn't speak English. The Dodgers knew that the first black in baseball would be forced to face a firestorm of racial hatred, so they looked for someone as articulate as he was talented - a man who could describe his ordeal and thereby win public support.

Jackie Robinson was that man, and he deservedly went on to become a hero. Meanwhile, poor and uneducated, Garcia isn't even a footnote in the record books.

Before and since, the Latin story has barely registered in newsprint or in the American consciousness. Rather, it has been told in bits and pieces, bogged down by fractured translations. Or it hasn't been told at all.

A testament to this can be found in the archives of the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame, in Cooperstown, New York. There, in voluminous files on every major league player, the history of Latins is scattered across a piecemeal collection of faded clippings containing statistics, a few clichés, some broken English, subtle racism, and passing references to life "south of the border."

"I think there is a general sense of inferiority of Latin cultures," says Jules Tygiel, author of the heralded Jackie Robinson biography, "Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and his Legacy."

"If you go back and read the way these players were covered, it was full of stereotypes...While it's probably not what it was years ago, the American players - both black and white - get more endorsements and the fans relate to them more than the Hispanic players.

"There is that type of prejudice."

Indeed, who remembers the first Latin player? And who realizes that he arrived in America 45 years before anyone ever even heard the name Robinson?

That player was Louis Castro. Slight, swift, he was 25-years-old when he signed with the Athletics in 1902. Some think he may have been Colombian, others Venezuelan. But little more is known about him, except for a few paragraphs at the Baseball Hall of Fame: "Louis Castro played 42 games for the Philadelphia Athletics and disappeared..."

Legend has it that he is buried somewhere in San Juan, Puerto Rico. No one knows for sure.

But certainly, his missing grave is a fitting metaphor for the Latin experience, a stark example of how it is so different from any other in baseball. For while American players of color have moved forward in history, Latins have, in large part, remained stuck in time.

Consider Miguel Tejada, a top-rated prospect from the Dominican who signed with the Oakland Athletics' organization for only $2,000 in 1993 - $1,500 less than Robinson's signing fee with the Dodgers, 50 years earlier.

Contrast that with the experience of Ben Grieve, a 6-foot-4-inch, 200-pound teammate of Tejada's from Arlington, Texas, who signed with the A's for more than $1 million. This, even though he is rated behind Tejada in both talent and potential by the team.

"Baseball is a business, a 100 percent capitalist business, and if the opportunity is there for exploitation, there will be exploitation," says Felipe Alou, a Dominican who, as manager of the Montreal Expos, is the only Latin manager in the major leagues today.

"Why does this happen? Because of our Latin American roots."

After all, in Latin America, baseball is a religion practiced by the impoverished.

It is seen as a way out, an avenue toward social and societal redemption. And since the turn of the century, roughly 2,000 Latin men, seeking to escape Third World slums, mind-numbing hunger, violence, ignorance, exploitation and fear, have come to play baseball.

At any price.

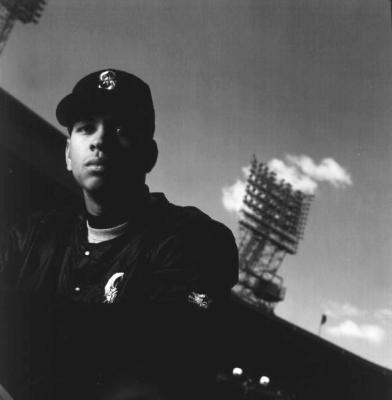

"The majority of people here admire baseball players. Women, children, everyone does. Even walking down the street, people say, 'Hey, how are you?'" relates José Paulino, a 19-year-old Dominican pitching prospect for the Athletics.

"People shout out your name because they know you live cleanly. They know you are someone who can earn money, someone who can help out your country."

Baseball was first brought to Latin America in the 1880s by U.S. servicemen stationed in Cuba. The game quickly spread to other Latin countries invaded by U.S. armies or co-opted by dominant American companies.

Early players were sugar cane cutters, banana pickers, fruit packers, rum makers, and cigar rollers. They would lay down their tools at the end of the day and practice for the entertainment of their bosses. They learned that swinging a bat didn't break their backs the way wielding a machete in the field did.

Turning their eyes toward the United States, 45 Latins between the years 1902 and 1946 became the first to invade what had been exclusively a white man's game. It's important to note that, while these players weren't black, some weren't exactly white either, and they provided a challenge to America's rigid perceptions of race.

At the same time, scores of talented Latin blacks were barred from the major leagues - men who often died bitter, poor and without the recognition of the players in the American Negro Leagues, now immortalized in books and films.

That changed after Robinson. Latins began to stand out on the field because the best players - blacks once banned from the game - were finally allowed to play. This period of the 1940s, '50s, and '60s marked one of the most fascinating and overlooked times in baseball history: The era of the black Latin players.

These men were segregated, persecuted, thrown at, spiked, struck from behind, released on a whim, and blocked from promotion to the major leagues just like American blacks. Yet these Latin players had the added burden of speaking little English and being from a different world.

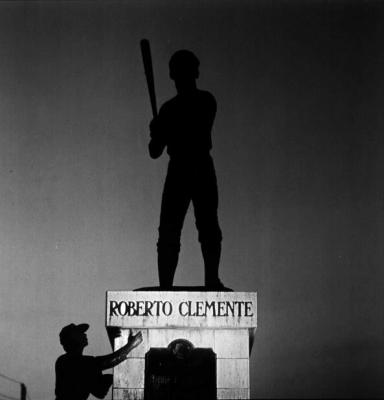

Their names are familiar: Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, Juan Marichal, Vic Power, Minnie Minoso.

And Zoilo Versalles.

The first Latin player to win a Most Valuable Player Award in 1965, Versalles' name was rarely, if ever, linked to his historical achievement. It wasn't even mentioned by the newspapers of 1965.

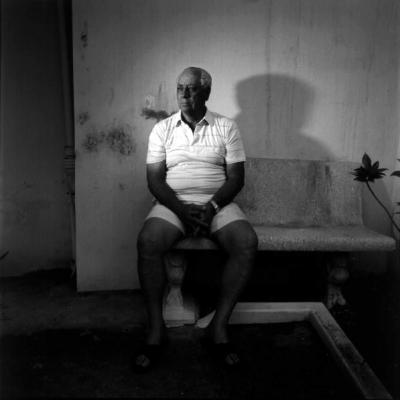

Eight years later, in an interview with sports columnist Jerry Izenberg, Versalles was asked what it meant to be a Latin playing in America's game.

The former street kid from Havana - at the end of a career that started brilliantly, but ended miserably - thought for a moment. Then, he spoke not only for himself, but for the thousands like him from the Spanish-speaking world:

"I am different. We, the Latins, are different. If an (American) boy cannot make a play or throw, he can go to his daddy, perhaps, and sell cars for him. But if I miss too many, where can I go when they say good-bye to me?

"I have no father with a business, no education...I must, therefore, make the play."