“A voice was heard in Ramah, lamentation and bitter weeping; Rachel weeping for her children…because they were no more.” Jeremiah, Chapter 31, Verse 15.

Gina's hands move constantly. She never looks directly at the other women around the table. Her frail frame and smooth skin make the 18-year old seem more child than woman. "I've cried and cried," said Gina. The other women nod sympathetically. " had my abortion on April 19 last year. It will be coming up on Easter. I know my baby is a boy. His name is Russell. His birthday is coming up and he is having it in heaven. I know he loves me."

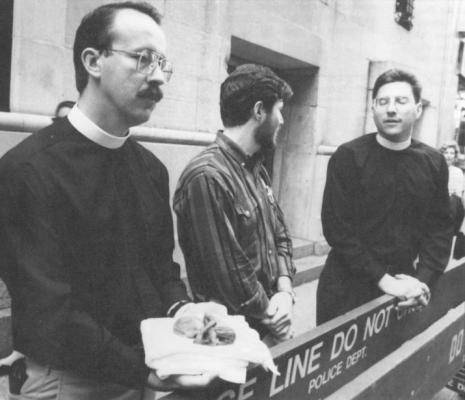

Wooden crucifixes punctuate the pale blue cinder block walls of the room where Gina is telling her story. A two-foot tall plaster model of the Christ child stands in one corner; in another corner, a piano; in the middle of the room, a table with two large coffee urns.This is the basement of the Catholic Center for the diocese of Bridgeport, Connecticut - until recently, a place where no one mentioned the word abortion.

But the six women in the room are participants in Project Rachel, a program run by the Catholic diocese to help women of all faiths work through their feelings over having had an abortion. The program's name comes from the Old Testament book of Jeremiah.

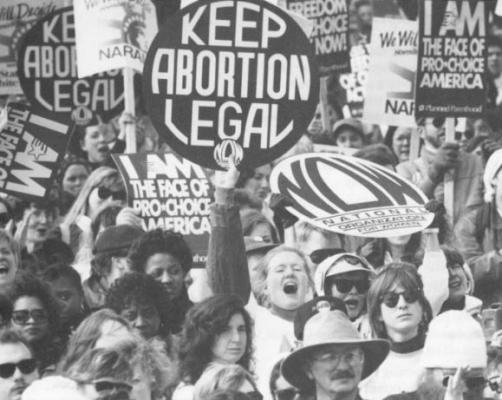

Little publicized and only slowly gaining acceptance within the Catholic Church hierarchy, Project Rachel groups exist in 80 dioceses in 40 states. The program is at the very frontier of what the. Church is doing to cope with the reality of abortion. Of the 1.6 million abortions annually, 32 percent are obtained by Catholic women. In contrast to the Church's public opposition to abortion, Project Rachel works at the grassroots level, reaching out to women who may feel estranged from the Church because they have had an abortion. By acknowledging that Catholic women have abortions and designing a ministry to help them, the church is sending a cleat- message that a woman can have one and still return to the fold.

However, the program sends a mixed message. While it reaches out to women, it does so within the context of the Church's centuries old doctrine that presents abortion as a serious sin. The program has two parts: a support group which meets once a week and individual spiritual counseling with a priest. Women are not compelled to do both, but they are urged to. Even so, conservatives within the church fear that the church is forgiving women too easily.

It is no accident that Connecticut is one of the states that has the program. It is the third most Catholic state in the country. Paradoxically, it also has some of the nation's most liberal abortion laws. In 1990, state legislators adopted the principles of Roe v. Wade. The Connecticut Catholic Church's flexibility is not restricted to abortion; in 1991, the Church signed off on a gay rights bill.

What is happening in Connecticut with Project Rachel is occurring in different ways throughout the American Catholic Church as it struggles to confront the real world in which Catholic people live.

In politics, especially in states with strong abortion rights laws and sentiments, the Church can remain a player only if it finds programs that adapt Church teachings to genuine needs.

"In a Catholic state we want to show we love the sinner and hate the sin," said Monsignor Martin Ryan, who spent the last 10 years in Bridgeport working to involve the diocese in the community's pregnancy prevention efforts and started the local Project Rachel chapter. "In order to speak to abortion today you have to offer a whole potpourri of services: physical and psychological," said Ryan. He is adamant that the Church needs to set an example of generosity if it wants society to listen.

Ryan's views are hardly typical. Most priests are not sure how to talk about such a forbidden subject. "A lot of priests care, but they feet they don't know how to be compassionate to women without going Soft oil the sin of abortion," said Father Michael Mannion, who leaches post-abortion healing techniques to priests and has lectured in dioceses across the country.

Renee, a member of the Bridgeport Project Rachel, spent six months looking lot a priest. The 43 year-old Hispanic woman, who dresses in designer clothes and a fur coat, had tier abortion five years ago when her First three children were in their teens. She felt She could not face bringing up a fourth child. Especially since she knew the burden Would fall mainly on her, because her husband, an executive with a Fortune 500 company, traveled frequently.

As soon as she got to the clinic she began to have doubts but she asked for a general anesthetic during the abortion. When it was over, she felt relieved. But within two days, guilt set in. She went to a priest, "he said, "Forget it. You are forgiven, just go ahead,"' she recalls and remembers feeling better. "But by the next week I felt terrible again. I went back and confessed all over. he said the same thing." Without success, she went to different churches in search of a priest who would make her feel absolved.

Although brought up Catholic, Janet's abortion Seemed easy. She was engaged to the child's father at the time, but they were not ready to start a family. She paid $160 at the clinic door, had the operation and banished the experience from her mind. That was 1976. Five year later, pregnant with what is now her eldest son, she began to have a recurring dream. "I Was lying in a hospital and my obstetrician was there with a team of doctors. They delivered my baby and he would be dead." A few years later, she had a miscarriage. which she took to be God's punishment for the abortion; then anxiety attacks began. She went to a priest to make a. confession. It was the first time that she had talked to anyone except her husband and one friend about the abortion.

He said, "It's a good thing you Came because now there is a chance that you might not go to Hell, if, if you're really sorry,'" She recalled. "It Was awful, bill I needed to talk so badly and I asked if I could talk to him some more. He said, 'No.'" It took almost three years for her to turn to another priest. "I watched this one for six months, to size him up." The priest sent her to a project Rachel group in Naugatuck, Connecticut that met in various houses. Eventually she joined Bridgeport's chapter.

Only two women attended the first Project Rachel meeting in Bridgeport in 1986, but since then about 70 women have participated in it for periods ranging from one month to six years. Protestants and Jews are welcome, but it is Catholic women who tend to seek out Project Rachel. Although the church emphasizes the spiritual counseling, the support group sessions draw the most women.

Pat Maurer, who runs Bridgeport's Project Rachel chapter, works for the Catholic diocese. She got involved with the program at the request of Monsignor Ryan who felt She had an empathetic Manner. Maurer herself has never had an abortion, nor does she have any training as a psychological counselor. She comes to each session with a carton of the popular religious book - Abort ion and Healing - and a shopping bag of tea, Swiss Miss Cocoa and instant coffee.

Maurer turned to Janet, who is a newcomer, to start the discussion. "We do not talk here about the sin of abortion. The Catholic Church doesn't condone abortion and you don't want to hear it's OK because you know it wasn't OK. If it was OK, you wouldn't be in the mess You are in now."

Janet nodded and wiped her hand across her eyes. "All you know is you feel like a piece of shit," Maurer continued. "And it weighs on your chest like a ton of bricks when you wake tip in the morning. You've got pain and guilt and depression coming out of every pore in your body. You have to be sad, you have to hurt and you have to cry. No one ever gave you a chance to grieve."

Most of the women nodded as she talked. Gina stirred her cocoa. "I didn't used to cry but I cry all the time now," said Linda, an 18 year-old with short blond hair who was quiet during the sociable half hour before the session began.

"When it happened, I stuffed it," said Janet. "After I had my first child I kept being afraid he would be run over by a car." Diane, a woman sitting across the table reached her hand out to Janet. Maurer looked understanding. "You need to know you're not a bad person," Maurer said. "You're not evil It's a very common feeling: women will often fear that God will punish them. But the instant that you had all that remorse, God, whoever is your God, God has forgiven you."

Words of advice poured out from longtime participants: name your aborted children; write them letters; hold a mass for them or a funeral. "I write him letters and I write him stories," said Gina. Several women nodded. They talked about their aborted children - Cynthia, Michael, Russell, and John - as if they were alive. "The women have an uncanny ability to predict what the sex of the child is," Maurer said. This, despite the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists's, assertion that without a sonogram or genetic testing, it is impossible to know the sex.

There is no discussion of politics, nor of the horrors of abortion - the usual rhetoric associated with the Catholic Church and the anti-abortion movement. In interviews afterwards only two women said they would like to see abortion banned. Most women wished that their pre-abortion counseling had told them how painful the aftermath of abortion could be. But most of the women agreed that at the time they decided to end their pregnancies, no one could have dissuaded them and some said that even today, they are not sure they would want the child.

"I feel ashamed but the abortion wasn't the worst thing in my life," said Frances, whose abortion was 14 years ago. She is an elementary school teacher who has been married twice and recently had a daughter. "The worst thing in my life was losing my husband through divorce. The abortion drew us closer together again for a short time. I still don't wish that I had that baby. I wish I hadn't had to have the abortion. I wish I hadn't gotten pregnant."

Maurer looked faintly uncomfortable. "Well you had other things on your mind maybe, with the divorce," she said. In the end, the group sessions come off as a combination self help course, group therapy and spiritual renewal class with an overlay of guilt reinforcement.

For Catholic conservatives, Project Rachel and other pregnancy counseling programs are the first step down the slippery slope of accommodation that leads to a softening of the Church's stand on abortion. Outsiders, however, say that the Church is not doing enough to cope with the problem of preventing pregnancy, which would be a key to reducing the number of abortions.

The National Conference of Catholic Bishops, which represents the Catholic Church hierarchy in America, gives arm's length approval to Project Rachel. But it does not promote it as part of its $1.35 million annual efforts for anti-abortion education, lobbying and public relations. The reason for giving it a low profile is that the bishops' conference does not get involved in programs that work directly with parishioners, said Helen Alvare, the bishop's spokeswoman on abortion issues.

Politics also may be a reason. Conservative Catholics wield tremendous power in the Church. Supporters of the program and other Catholic liberals are still reeling from the Vatican's censure of Milwaukee Archbishop Rembert Weakland under whose auspices Project Rachel was started.

In 1990, Weakland, one of the church's most outspoken figures on behalf of women, held a series of hearings on abortion, primarily for Catholic women. The 900 women who participated were asked to consider even such taboo questions as whether there were circumstances when abortion should be permitted and whether there were possibilities for compromise in the Church's position.

A year later, when the prestigious theological faculty of Fribourg University in Switzerland awarded him an honorary doctoral degree, the Vatican refused to allow him to accept it. In a letter denying him the degree, a Vatican representative noted that Weakland had "recently taken certain positions relative to abortion which are causing confusion amongst the faithful in the United States."

Even in liberal Connecticut, it has not been easy to build support for Project Rachel. Today, the only chapter is in Bridgeport, Father Thomas Barry, who heads up abortion-related activities for the archdiocese of Hartford, the slate's largest diocese, described the program with pride. He underscored that he presented it to the state's priests at the annual clergy education day a couple of years ago. Their reaction was mixed. "I think some people are set in their ways," said Barry, "and it's difficult to adapt to a sensitive pastoral role when, in the past, ministry was more functional."

But is post-abortion counseling really necessary? Most psychologists and psychiatrists think not. They say for most women abortion is more therapeutic than traumatic. And, they question the Catholic Church's involvement in post abortion counseling, viewing it as an after the fact effort to alleviate guilt that the Church created. "The cause of women's stress after abortion is their guilt," said Terry Beresford, a psychologist who has worked in clinics since abortion was first legalized in Washington, D.C. in 1970. "Arid how did the guilt get there? From the Church and now the Church is going to help them deal with the guilt that the church produced in the first place. It's so ingrown."

However, Beresford's approach is little help to Catholic women who have had abortions and still want to feel they have a place in the Church. Other psychiatrists see it as potentially useful to women who wart to reclaim their sense of faith. "If You are a committed Catholic and that's an important part of your life, then anything that helps you feel whole again in your faith is lovely as long as it doesn't reinforce the guilt," said Nada Stotland, a professor of clinical psychiatry, obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago. Stotland studied abortion in private practice and during the years when she chaired the American Psychiatric Association's committee on women's issues.

Mainstream psychiatrists and antiabortion therapists have a rare point of unanimity on the statistics they rise to support their positions on the significance of post-abortion trauma. Abortion rights psychiatrists say that while 40 percent of women who have abortions suffer some sadness in the weeks after terminating the pregnancy, within six months only one to three percent continue to feel distressed. Is this many women or few?

Anti-abortion therapists talk about it in terms of numbers. "There are 1.6 million abortions a year, so it doesn't take a very large percent to mean we're talking about a lot of women," said Wanda Franz, the recently elected president of National Right to Life, who is a psychologist.

In the diocese of Milwaukee, where Project Rachel started, counselors average two calls a week from women interested in attending the program, said Vicki Thorp who runs the national Project Rachel office there. Altogether, about 8,000 calls a year come into dioceses around the country - or about one half of one percent of the women who have abortions, Thorp estimates. Add the women who call into similar Protestant programs and the number jumps to more than 16,000.

But ultimately, statistics are irrelevant. For the women in the basement of tile Bridgeport Catholic Center, sadness cannot be calibrated in percentage points. They live in a world of ghosts. Days are fraught with meaning - the day of their abortion, their child's name day, the day it would have been born. The children they aborted are with them each time they become pregnant, become mothers and as they raise their children.

"This is the ultimate one thing that cannot be redone," said Renee, who has a mass said for her child Michael each year on Sept. 29, his name day. "But now, after coming here, I feel I have placed my child where he is safe."