The Midwest: An Unlikely Laboratory For New Towns

The Midwest: An Unlikely Laboratory For New Towns

Leonard Downie, Jr.

Minneapolis, Minn.

September, 1971

Freeways came late to the urban Midwest, after they had been tried to relieve traffic congestion in the crowded East and had created an entirely new pattern of living in California. Today, the multi-lane divided highways marked by prominent blue and red interstate route signs dominate the metropolitan landscapes of Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago and Minneapolis. And they all seem to be carrying more and more people out of these cities into the vast suburban areas around them.

Yet as fast as those suburbs have been growing since World War II, most now trends in housing have also come slowly to this region. The single-level “ranch type” home now seen everywhere here was imported from California, for instance. Condominium and cooperative ownership of apartment units, still considered a daring idea of the future among Midwesterners, has long been popular along the East Coast.

Now, the developers of an ambitious real estate project named Jonathon are trying to sell the notion of transforming a swatch of scenic Minnesota countryside containing idyllic blue lakes and low green hills into a “new town” southwest of Minneapolis. The new town concept – starting from scratch to create a complete, new planned community of homes, schools, recreation, commerce and industry with some unifying design or identity – is already familiar to residents of the East and West Coasts, where the large and growing new towns of Columbia, Maryland, Reston, Virginia, and Irvine, California, among others, are located. Yet it was not until this summer that Jonathon and the first two other Midwestern ventures considered to be new towns began to take shape sufficiently to attract wide notice.

After overcoming initial financial problems, Jonathon is now far into construction and sales of modern design houses, townhouses and apartments for its first 10,000 residents. This first of five planned neighborhoods is being built around one of Jonathon’s four tree-lined lakes on grassy hillsides traversed by bicycle and foot paths. In a meadow a short drive away, several firms have built small modern offices.

Thirty-five miles from Jonathon, in downtown Minneapolis, construction began this summer on the first “new town” inside an American city. Cedar-Riverside, named for the two major streets that intersect at its center, had been a badly rundown neighborhood on a triangle of land isolated by two freeways and the Mississippi River. It is now to become a self-contained new inner-city community of apartments and decked malls, complete with schools, shopping and entertainment, around an expansion of the campus of the University of Minnesota.

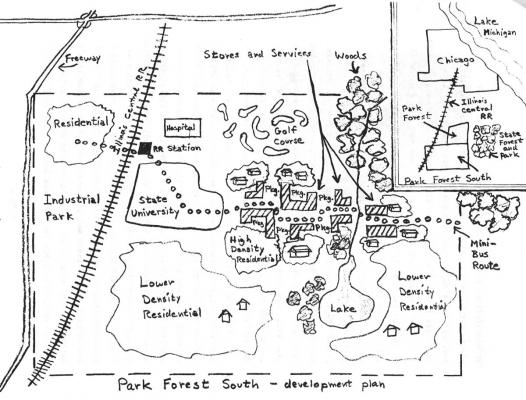

In another part of the Midwest, 30 miles south of downtown Chicago, the most ambitious of the three new towns began to rise this summer on flat, partly wooded farmland bordered on the west by a railroad running to the city, on the north by the previous outer ring of suburban growth, and on the east by a state forest preserve and park. An experienced planned community developer bought up the remnants of a small unsuccessful traditional subdivision of single-family house and has already added clusters of futuristic apartments and townhouses linked by walkways that go under the roads to schools, a community swimming pool and recreation areas. This is the first neighborhood of a huge new community, now called Park Forest South, where large industrial plants and a new state university are also being built.

Although they are not the first of their kind in the country, Jonathon, Cedar-Riverside and Park Forest South all have already won commitments from the federal government for financial backing under the “new communities” provisions of recent housing laws. This legislation was designed to encourage planned development of complete new communities in place of the meandering bedroom subdivisions that have characterized suburbia in the United States until now. Each Midwestern new town project will become a laboratory for urbanologists who believe that by planning carefully they can avoid the problems of overgrown cities and yet retain the advantages of city living – such as nearby jobs, shopping, recreation, cultural resources and diversity of lifestyles – which most add-on suburban subdivisions cannot offer. At the same time, they want to avoid in new towns the destruction of environment and waste of land caused by most helter-skelter suburban growth.

Jonathon was the first new town in the United States to be selected by the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for the federal guarantee of financing for acquiring land, putting utilities underground, building roads, constructing housing and providing community services ranging from bus shelters and small developed play areas to recreational lakes and shopping centers. Soon after, Cedar-Riverside became the first inner-city project picked by HUD for federal new communities’ backing. Each of the two, along with Park Forest South, promises to develop and test fully a different interpretation of the new town vision as an alternative to both inner-city decay and suburban sprawl.

Jonathon

Jonathon comes closest to exemplifying the “garden city” ideal of Sir Ebenezer Howard, the 19th century Englishman whose writings inspired modern new town building. Howard wanted to return the city dweller to nature by carefully fitting new urban communities into the rural countryside and preserving in and around them open air, greenery, wildlife, pleasant views and outdoor recreation. His writings, championed by planning idealists in the United States during the 1920’s and 1930’s, led to the development of a relatively few “greenbelt” communities, such as Greenbelt, Maryland, near Washington, D.C., and Radburn, New Jersey, that put their residents in close touch with green grass and flowers and fostered the concept of community open spaces to be shared by homeowners and renters. But at the same time, each lacked the size, commerce, employment and other resources necessary to offer a real alternative to city living.

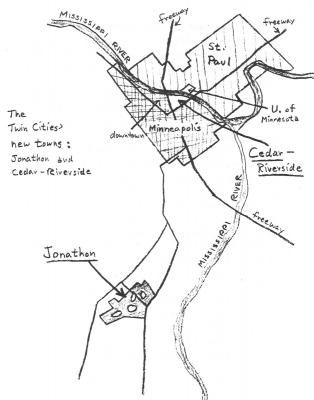

The Twin Cities, new towns: Jonathon and Cedar-Riverside

Jonathon is planned to pick up where the greenbelt towns left off. The project was begun by Minnesota State Senator Henry T. McKnight, a wealthy real estate executive and conservationist, who wanted both to preserve the beauty of the hills and lakes around Minneapolis and also find room among them for people like himself to live, and yet not be too far from where they worked and shopped. The site is quite beautiful and the first homes and apartments have been fitted in so that grand views of the countryside remain in all directions. Grass, trees, water and outdoor recreation are steps away from every door. The architecture thus far has made use of novel shapes and woodland-like colors to blend the buildings into the landscape. Even the developed sections of Jonathon still resemble the rural countryside around them. And this atmosphere is emphasized by Jonathon’s promotional material.

“People living with the land as well as on it,” the announcer says in the sales movie, an an attractive family gambols across the three-way split screen among the flowers, trees, grass, birds and butterflies.

“Jonathon is environment,” a sales booklet states. “One-fifth of all the space in Jonathon is permanently reserved for recreational use – woods, parks, lakes, tree-lined walkways.”

Wooden steps lead into and out of parklands. Stables, bridle paths and horses are there. An old barn and farmhouse are being turned into a community art center. Recreational facilities have been built alongside the lakes. The first “village center” of small shops and offices (mostly occupied by Jonathon’s developers and salesmen right now) has been designed to resemble a modernistic brown wooden barn with glass stall shops on the ground floor and offices in the loft. One group of startlingly different townhouses with natural wooden exteriors, appropriately named “Treeloft”, has been built right into a grove of trees on wooden stilts with wooden bridges and stairways connecting each unit’s varied living levels with the others and the ground.

At first glance, it appears that Jonathon is being built only for the eye – the eye that wants to see urban man and his trappings fade into the countryside. The strongest influence on its development, after conservationist McKnight, seems to be Ben H. Cunningham, an architect who is Jonathon’s “vice president/director of design.” A tall, handsome, tanned, urbane man who works out of a bare-beamed, cathedral-roofed office in the town center loft, Cunningham likes to talk mostly about design, and how he is experimenting with it at Jonathon, even though that sort of thing can be risky in real estate ventures.

“Many of the present homes in Jonathon seem extremely modern. Aren’t more traditional homes allowed?” asks a key question in a Jonathon sales brochure. A variety of styles is the goal, the brochure answered, so long as “good design is also encouraged.” Jonathon is, the booklet added, “drawing national attention for its pioneering in completely new types of housing.”

The inside of the small “town center” building, with its modern, barn-like design. Shops are being built into glass stalls downstairs and offices in the upper floor lofts (rear, above arrow).

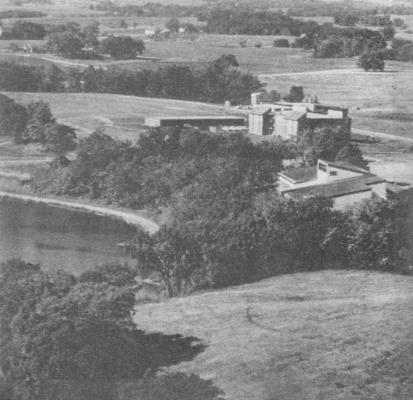

Even with many buildings completed, including the town center of shops and offices (foreground) and an apartment building (just behind the town center), Jonathon, with its lakes, trees and hills, retains a rural atmosphere.

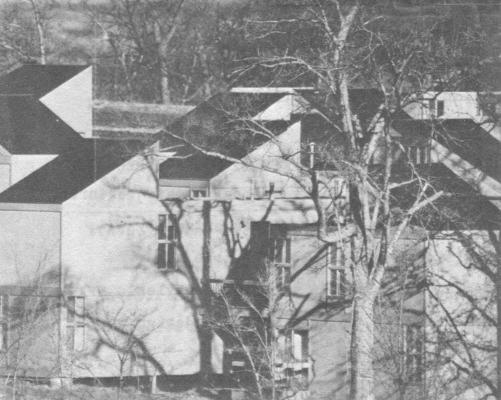

The “Treeloft” apartments, built on stilts with natural wooden exteriors, and designed to blend in with the trees all around them. Each unit has a different floor plan with varying living levels and many two-story rooms up among the trees.

At first, this notion did not catch on with conservative real estate financiers, Cunningham admitted. The first underground power lines, sewers and water mains were laid at the site and announcement of the project made in 1967. Homes were started in 1968. A year later, however, the developers were still looking for backers beyond the local businessman who had joined McKnight in the initial investment, and the tight money market was making investors even more difficult to find. To join up with one of the few willing banks, insurance companies and other financial giants, “we would not only have had to get in bed with these people, we would have had to marry them,” Cunningham said. “We didn’t want to give up that much control,” particularly over design.

The new federal housing legislation for new communities came along just in time to save Jonathon. Federal officials liked the project’s site, plans and unusual architecture. Overnight, Cunningham said, the federal guarantee had “an almost unbelievable impact” on the real estate community and gave the project both the financial safety and “credibility,” (to use Cunningham’s word) that could be sold to investors on Jonathon’s terms. Cunningham still worried that the federal government’s influence might jeopardize “preserving design concept and quality.” But he has been pleasantly surprised to the contrary, he said, and feels “not at all constrained by the HUD partnership.”

The question remaining is whether this architectural amd planning experiment can be made to work. The federal support is there. And most of the first few hundred dwellings were sold or rented even before they were finished. Their design and Jonathon’s setting certainly appeal to some. The problem could come, however, in trying to enlarge this attempt at an environmental utopia into a durable, thriving, complete community. There are already signs of warning, wear, tear, shortcomings and compromise everywhere.

It was necessary from the start, for instance, to experiment without losing money “in a real world,” as Cunningham put it. Because present inefficient construction techniques make most new design ideas quite expensive, corners were obviously out to keep prices down. The wooden balconies and bridges of Treeloft shake and clatter ominously as one walks across them. The settings of this and other imaginatively designed, relatively low-cost groups of townhouses and apartments are marred by long lines of garages that might have been hidden underground were not that too expensive. The outdoor decks, large glass doors and well-placed windows of many dwellings are off-set by quite small room sizes. Outdoor lines are marred by the protrusion of huge, ugly air conditioners and other hardware for which there was no room inside. The most appealing and durable looking homes in Jonathon are still the large, individually designed and built detached single-family houses in the $30,000 to $50,000 and up range, which hardly make the most efficient use of the land or offer housing to a wide range of income groups.

Federal officials were impressed that Jonathon already was building some government-subsidized housing for lower income families. But these rowhouse apartments are obviously inferior in design and construction to the rest of the community and are isolated in a remote corner of the project. Their handling hardly provides hope of any real integration of income groups in Jonathon, one important way in which new towns have been expected to differ from economically stratified suburbs.

Despite the extensive network of footpaths through open spaces, use of an automobile is still a necessity for almost everyone at Jonathon to go to the store or work, whether in the village center or industrial park, or all the way to Minneapolis. On a sunny Sunday afternoon that drew many residents to the lakeside for boating and picnicking, most of the people appeared to have shunned the footpaths in favor of driving along undeveloped dirt back roads to park on the grass in a meadow near the recreation area. For at least several years to come, the big department stores and such cultural resources as libraries, theater and movie houses will be 45 minutes’ driving time away in Minneapolis, with no public transportation available.

“There is no wall around Jonathon,“ Ben Cunningham said by way of explaining that its residents are free to make the drive to Minneapolis for cultural activities and other aspects of city life that “a community of 50,000 population cannot generate.” Yet this is precisely what has always seemed to be lacking in most suburban communities, and Jonathon is farther than most Minneapolis suburbs from downtown. A big regional shopping center for Jonathon’s now vaguely planned town center of the future will come later, Cunningham said. And a new executive has been hired to “worry about software services,” such as education, day care for children, community political activity and the like, which have taken a back seat to the question of design.

Cedar-Riverside

Those things that have been treated mostly as after-thoughts in Jonathon’s development – economic integration, cultural resources, education and daycare, diversity of commerce, social services, health care, automobile storage, and the possibilities offered by new technology – are just what the developers of Cedar-Riverside in downtown Minneapolis decided to plan for first, before any new buildings were designed or concrete poured. One reason for this is its location inside the city, near a major university, a smaller college and two hospitals, and not far from the commercial center of a large metropolis. But another reason is that its developers are really amateurs in the real estate field who are interested first in the cultural and human diversity of city life. They are concerned as much or more about what people would do everyday in a new Cedar-Riverside as they are about what people would see in the way of wood, bricks and mortar. They want primarily to show that high-density urban living can be an advantage for Cedar-Riverside residents, rather than something from which to flee to the countryside. Their experiment is worth study not only as a test of this proposition, but also as a unique application of one of the most dishonored U. S. government techniques: urban renewal.

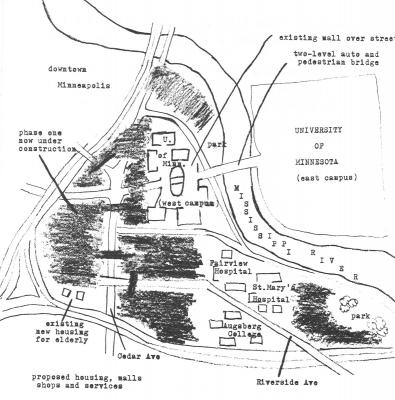

University of Minnesota (east campus)

Cedar-Riverside began not as a developer’s carefully planned land scheme, but rather as a housewife’s whim. One evening in 1962, Gloria Segal – who describes herself as a mother of four, wife of a prosperous Minneapolis doctor and active civic worker who knows Hubert Humphrey – had great difficulty finding a place to park to attend a concert at the University of Minnesota. With the advice of a business professor friend, Keith Heller, she promptly bought a lot for parking just across the river in a rundown neighborhood, populated mostly by alcoholics, barkeeps and student dropouts, where the university was planning to expand. After a while, she and Heller decided to buy more land and put up a decent new apartment building. But before starting to build, they found themselves buying still more land for a larger development with financial support from friends and small bank loans. Finally, with the help of Ralph Rapson, now head of Minnesota’s School of Architecture, they realized that they had an opportunity to do something much more ambitious than putting up a building or even several buildings.

By this time, Cedar-Riverside’s 340 acres had been cut off from the rest of Minneapolis by freeways on all sides but the one bordered by the Mississippi, and the University of Minnesota was expanding across the river into Cedar-Riverside from its main campus on the east bank. It was already building its new library on the west bank and plans called for eventually housing half of the university’s facilities there. The rest of the land in the neighborhood was selling cheaply at the moment, but a big new market for housing was being built in by the university’s expansion and Mrs. Segal and Heller saw the threat of real estate exploiters buying as much land as they could and building inexpensive walk-up apartments – sowing the seeds for future slums.

It turned out that Minneapolis city officials saw this possibility, too, and moved to prevent it by declaring Cedar-Riverside an urban renewal area. In other times and cities, of course, this step has not always meant creation of a viable community, but more often has produced other kinds of instant ghettos for various income groups, ranging from the very poor to the very rich. So the Segal-Heller group kept buying property on their own. By 1968, when the area became an official urban renewal project, they already owned 75 percent of the land not earmarked for expansion of the university, the two hospitals, a small college or parkland.

By that time, they also had a plan – a startling plan for rebuilding there a new community that would really integrate all income groups and attract the kind of shopping and culture that make city living appealing to people like Heller and Mrs. Segal. The plan is the work not only of architects but also experts in the fields of engineering, energy, social planning, economics and environmental design. One consultant was Heikki von Hertzen, founder of the well known satellite new town of Tapiola in Finland. Amd their product is far more than a land-use plan, although it is ambitious in that way alone by proposing to fit 30,000 people, along with schools, stores, open spaces, malls and other facilities, on just 100 acres of usable space (compared to the goal of 50,000 people on 8,000 acres for Jonathon).

Elevetated Plaza/Walkway System

It is also a plan for completely separating pedestrians from all automobile traffic, and even the sight and sound of cars, by building the entire neighborhood above the streets, with cars driven and parked under the pedestrian levels is a series of decks. It is a plan for economically heating the entire community, including outdoor shopping areas, from a few central locations is various neighborhoods in a technological experiment to be tried by the local gas company. It is a plan for making maximum use of cable television for broadcasting, intercoms, public security and schools by laying the cable before building construction begins. It is a plan for housing lower income families alongside upper income people on the same floors in the same buildings, with rents varying as such as from $50 to $500 per month. It is a plan for providing community health care for Cedar-Riverside residents at a facility to be set up by the two hospitals there. Finally, it is a plan for keeping in the neighborhood everyone who presently lives there, including the alcoholics and dropouts, along with the artists, students, teachers and the elderly, even as the new apartment buildings attract thousands of newcomers to the area.

How the cars would be “tucked under” pedestrian malls in the Cedar-Riverside plan.

The plan has won approval from both urban renewal officials and the new communities’ office in HUD. Although building did not begin until this summer, preparations have been going on for years. The new development is being phased so that only one part of Cedar-Riverside is being torn up at any time. Residents of an area being cleared have been slowly relocated to other renovated housing of their choice in the neighborhood. For a group of elderly men, this meant thoroughly rehabilitating a large old rooming house because they refused to be moved into new high-rise housing for the aged built by the city on the edge of Cedar-Riverside, where mostly elderly women live. Since the mid-1960’s, Heller and Mrs. Segal have been landlords for nearly 4,000 people in the old Cedar-Riverside housing they bought and repaired until the redevelopment is completed. A large force of maintenance men and social workers has helped them tend this flock. No rents have been raised for any of the tenants, even in buildings the two bought several years age. Each tenant pays what he can afford, and that amount frequently varies by as much as $100 from one identical apartment to another in the same building.

Mrs. Segal helped bring to Cedar-Riverside theater and dance groups that now draw pupils and patronage from throughout the Twin Cities area. New shops of all kinds, attracted by low rents and other support from the Heller-Segal group, have brought the area’s commercial streets back to life. Vacant lots have become small parks cleverly furnished with items made out of old sewer pipes and tires.

The construction started this summer is for the first group of high-rise buildings and connecting malls for 3,000 people just in back of the Cedar Avenue shops. Above lower levels for auto traffic and parking will rise a 25-story luxury apartment building, a taller 40-story building for middle and lower-income tenants scattered without pattern throughout it, another building for public housing tenants, clusters of townhouses, stores, offices, schools and such community facilities as day care centers, each connected to the other by pedestrian malls and foot bridges over the streets. The developers refused the cash federal subsidies they could have received for building the housing for poor families; instead they asked that it be spent for the pedestrian bridges and mall walkways. Urban renewal and city funds are providing public utilities and street improvements.

Mrs. Segal said she hopes that by “tucking the automobile underneath” and mixing tall buildings and malls to give almost everyone an open view, Cedar-Riverside can minimize the disadvantages of high-density living while retaining the advantages. Donald Jacobson, chief planner for the project, wants to use what he calls a “fresh start” on development inside a city to demonstrate not only different housing forms, but also new modes of communication, new kinds of energy systems and new settings for learning. This opportunity has been wasted in most urban renewal projects in the past, and is still not being taken advantage of fully in most new planned communities in the suburbs. Jacobson is most proud of the experiment in placing low and high income families side by side on the same floor of the same building, perhaps the boldest and riskiest idea being tested in Cedar-Riverside.

The Heller-Segal group prides itself on doing what everyone had thought impossible and learning as the project goes along. Their staff lunches together every day in a clubby atmosphere in a room filled with planning maps at the center of the renovated ice cream factory that now houses their offices (even the plastic placemats are detailed reproductions of the Cedar-Riverside plans because, as one planner explained, it is the usual topic of luncheon conversation). The mood there is one of urban real estate evangelism. Yet it is the very one-of-a-kind opportunity that Cedar-Riverside presents that also limits it, except for the technology it tests, as a model for either urban renewal projects or new towns elsewhere.

The relocation into temporary housing of all the old residents would be hard to duplicate, for instance, in the huge Shaw urban renewal area in Washington, D.C., where tens of thousands of large, poor families live in highly overcrowded conditions. Few large families live in Cedar-Riverside, which actually lost population in recent years. The problem was small enough to be dealt with and not so urgent as to rush what has been a slow, emerging creative development process. The prospects of successfully placing rich and poor side by side also are certainly much better in a university-dominated neighborhood, where the poor will still be an acceptable minority, than it would be in the middle of a large ghetto paralyzed by problems of crime, narcotics, poverty and race.

Cedar-Riverside is perhaps uniquely benefited by the presence of a large, cooperative university with its built-in market for housing, supply of jobs, source of culture and atmosphere of stability, along with two large hospitals nearby. Few inner city neighborhoods in such an ideal location would also contain land available at so low a price as it was when Heller and Mrs. Segal were buying it up. And few, if any, ex-urban new town sites would likely come with any of these benefits, or government-supplied streets and utilities. In these ways, Cedar-Riverside not only would serve poorly as a model for new towns elsewhere, it scarcely fits the definition of a new town itself. It still promises to serve, however, as an important laboratory for many of the experiments in urban design and living proposed in its ambitious plan.

Park Forest South

The developers of the third Midwestern new town, Park Forest South, outside Chicago, are trying to build some of these big city benefits into their project, as well as a flavor of Jonathon’s garden city environment. Like Cedar-Riverside, Park Forest South will contain a large university (Governor’s State, now being built on land donated by the developer) and is to have a large downtown shopping and community service district with pedestrian as well as automobile access to it. And like Cedar-Riverside, it is to be a community mostly of multi-family housing, although not nearly so densely built up.

Like Jonathon, Park Forest South is being built on an attractive rural site, the chief natural assets of which are thickly wooded areas on the site itself and an adjacent state forest preserve and park. It also will offer plentiful outdoor recreation. But, except for wooded areas that are to be left alone, less land will be kept entirely open in Park Forest South, where twice as many people (100,000) are to live on the same number of acres (8,000) as in Jonathon. Unlike Jonathon, Park Forest South will have direct access by rapid public transportation to its parent city, and will be built right up against another suburban community, which at first will provide the major department stores, large library, community theater and art, and well-organized schools and recreation facilities that Park Forest South will not have until later. That adjacent community, Park Forest, is in more ways than just this one the parent of Park Forest South.

The developers of Park Forest – Philip Klutznick, a former federal housing commissioner, and Nathan Manilow, millionaire developer of housing subdivisions, apartments, offices and hotels in Illinois and Florida – took a $50 million federal loan guarantee obtained by Klutznick and built during the 1950’s the largest, most attractive and workable planned community of its time in the United States. Today, about 30,000 people live on 3,500 acres in Park Forest, mostly in single-family and duplex homes, surrounded by abundant trees, shrubs, flowers and grass on winding streets that lead in orderly well-planned fashion to several large well-developed city parks, innovative schools in educational parks (complete with adult education facilities and year-round recreation centers), and perhaps one of the most attractive open air shopping centers in the nation. Built around a meandering plaza of lush greenery, the shopping center contains major department stores, smaller shops and business offices in attractively designed low buildings that protrude out into the well-landscaped parking areas that look more like a pattern of city streets than the usual sea of parked cars. It is a lively, human place that along with a large town library, several churches, city hall and indoor community swimming pool around it give Park Forest an inviting, coherent town core unmatched in America’s suburban sprawl. Its identity may be strictly middle class, and much too sterile for city lovers (as well as Park Forest’s newly grown up teen-aged generation, which finds too little to interest it and, as a result, is the cause of the town’s most serious problem, juvenile drug abuse), but Park Forest does have an identity and order to it that well pleases its residents, a claim few other suburbs can make.

Part of the shopping center-plaza at Park Forest, with the clock tower, a community landmark, and the attractive landscaping.

Park Forest also pioneered in providing housing for lower-income families in clusters of still attractive brick rowhouses arranged in park-like settings with large community green spaces between them. The developers, who built almost all of the town’s housing themselves, still rent many of the rowhouses at comparatively low rents, while others are owned by cooperatives formed by their tenants. Although black people still are a decidedly small minority in Park Forest, they were able to buy and rent homes there long before they could got into any of Chicago’s other predominantly white suburbs.

Park Forest South (a provisional name soon to be replaced by another selected by its first several hundred residents) was begun by the same Nathan Manilow who built Park Forest. He has been joined in this new venture by the Illinois Central Railroad, which operates the highly successful commuter and freight line connecting Park Forest South with downtown Chicago, and United States Gypsum, a leading manufacturer of construction wallboard. Park Forest South, then, is essentially a second generation new town, building on the experience of Park Forest. And the man now in charge of its everyday progress, Nathan Manilow’s son, Lewis, is a rare second generation developer.

With his carefully trimmed beard, shoulder-length curly hair and rimless glasses, Lew Manilow, sitting inside an office crammed with modern paintings, graphics and sculpture and offering visitors some of his usual luncheon of roast beef sandwiches and diet cola, more nearly resembled an avant-garde university professor than a real estate tycoon. His conversation quickly revealed the education he received at the University of Chicago and Harvard Law School, before working as a government prosecutor and a lawyer in private practice. His obvious knowledge of his business and energetic, impatient manner bore evidence of the other years he spent working with his father on family real estate projects. It soon became clear that Lew Manilow possessed the rare, perhaps unique combination of the hard-headed dynamism of an ambitious builder and promoter and a philosophical detachment, intellectual development and broad perspective markedly uncommon in the real estate world. His plans and ideas for Park Forest South include the same interest in new design and concern with environment as those of the developers of Jonathon; some of the bold thinking about new technology and conservation of the advantages of urban life shown by Cedar-Riverside’s new founders, as well as the pragmatism about what can be done successfully that made James Rouse’s Columbia, Maryland, new town and Nathan Manilow’s Park Forest work financially while breaking new ground.

Park Forest South – development plan

Manilow’s designers are concerned about minimizing the role of the automobile in Park Forest South, for instance, but they also have found that suburbanites want their car or cars close to their front door every day. “We can’t just ban cars or put the parking 500 feet away or underground somewhere. People won’t stand for that,” Manillow said, citing the streets crowded with parked cars in English new towns, where little planned parking was provided. So his designers are experimenting with proposals to use fences, foliage or buildings themselves to screen off cul-de-sacs where residents’ automobiles will be parked. Unlike Columbia, Jonathon, or any other satellite new town built to date, however, Park Forest South will be able to offer a viable alternative to automobile commuting to the nearest big city. A commuter station on the Illinois Central line is being built right in the middle of Park Forest South, with the huge industrial park on one side of the tracks and the rest of the development, including the new university and a planned hospital, on the other.

A linear downtown, much like the commercial streets that Cedar-Riverside is being rebuilt around, is planned for Park Forest South, to run from the railroad station past the university and hospital on through much of the residential area. Manilow pointed out that this dense development of stores, offices, apartment buildings, city hall, police and fire stations and other community services will be accessible to many more residents by foot or bicycle than would be a circular downtown core surrounded by one big parking lot, such as the one in Columbia, Maryland. It Is being designed so that fingers of shops, community services, recreational facilities aid pedestrian bridges or malls will reach out through or over parking areas right up to clusters of apartments and townhouses to encourage pedestrian use of the downtown area. A mini-bus system also is planned to run through the downtown area from one end to the other, connecting with the railroad station. Manilow said he wants Park Forest South, despite its suburban setting, to offer in this way a taste of city living to adult residents. The alternative, chosen by Columbia and most other new towns, is to group housing around schools and recreation, a convenience primarily for children, and to build central shopping centers accessible only by car.

A view of the first small cluster of townhouses and greenery at Park Forest South.

This is just one way in which Park Forest South also will move a step beyond what was done in Park Forest. Another is the use of open space. Manilow said the large community green spaces in the lower income housing neighborhoods of Park Forest are seldom used. They are two small for ball-playing and too big to be thought of by the residents as useful for anything except the view. This is why, Manilow said, the community open spaces between clusters of buildings at Park Forest South are smaller and more densely filled with small playgrounds, benches and the like.

While Park Forest is principally a bedroom community for commuters, Park Forest South will provide a great number of jobs at the university and in its industrial park. A pharmaceutical firm has already begun building its world headquarters in the industrial park, where strict land covenants enforceable in court will require each plant to conform not only to architectural and landscape guidelines but also to limits set on noise and emissions into the air and water. The new community’s sewage and water system, owned by the developers, includes one of the most advanced tertiary treatment facilities to preserve a bountiful supply of water located under the Park Forest South site. Cable television communications systems are also being planned, as well as a community health care and insurance plan patterned on the one started successfully in Columbia, Md.

Although he is quite eager to try these and other ideas out in Park Forest South, taking advantage of the opportunity to build from underground up in a virgin area, Manilow says he wants to avoid thinking in terms of the “new town mystique” that a utopia can be created without trial and error. He is trying, for instance, to preserve intact most of the site’s heavily wooded areas, but wants the freedom to remove some trees where he believes he must, in exchange for the many others he is planting. But “the woods people,” as he calls a few older remaining residents of the area who live near the forests, “keep saying how the developer, you know how they use that word ‘developer,’ is going to tear down all the woods.

“But I couldn’t do that if I waited to,” he said. “I’m still going to be here trying to sell this place to people years from now. I’m not about to do anything to harm my chances of doing that. That’s the advantage of the American system or new town building, both compared to the here-today, gone-tomorrow subdivision builder here in the past and the English system, where the government really controls everything.”

Manilow obviously enjoys the give and take with “the woods people,” as well as the rest of his daily struggle between what he and others would like a new town to do and what he believes can be worked out feasibly. The choices are bigger at Park Forest South than at Jonathon, the garden city, or Cedar-Riverside, the dream urban renewal project. Park Forest South could be some of each, or slide into another direction, and become only a more advanced middle class suburb, a latter day Park Forest. Because the matrix of possibilities is less confining at Park Forest South than at Jonathon, and less unique than in Cedar-Riverside, Park Forest South has much more potential than either of the other two as a model for consideration of future new town building. This makes its success or failure that much more of interest to all of us and that much more of a challenge to Lew Manilow.

Received in New York on September 27, 1971.

©1971 Leonard Downie, Jr

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, The Washington Post, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.